|

||||||

|

BombinatoridaeThe Bombinatoridae is a family of toads consisting of eight species in a single genus, Bombina. They are commonly referred to as the "firebellied toads", due to the bright colors on their bellies. Firebellied toads are distributed across Europe and Asia. The Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad is commonly found in the pet trade, and can be purchased in pet stores across much of the United States. |

Video Showing Heartbeat of Fire Bellied Toad |

|||||

Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad Tadpole. |

Underside of a Fire Bellied Toad tadpole |

Recently metamorphosed Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad. |

||||

BufonidaeThe members of the family Bufonidae are often known as the "true toads". Over 600 species are found in this group, and their natural distribution includes North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. One member of this group, the Cane Toad (Rhinella marina) has become an invasive species after being introduced to Australia, Hawaii and elsewhere. Although the Bufonidae look similar to Fire-Bellied Toads and Spadefoot Toads, they are only distantly related to these groups. In fact, the true toads are more closely related to the treefrogs (Hylidae) and true frogs (Ranidae) than they are to the Fire-Bellied Toads or Spadefoot Toads. Many of the true toads used to be assigned to the genus "Bufo". However, in 2005 a group of amphibian taxonomists proposed re-arranging the taxonomy of many amphibians, including toads. Although many of the proposed taxonomic changes are controversial, many of the changes to true toad taxonomy appear to have been accepted by much of the research community. Many of the North American toads pictured below were formerly assigned to the genus "Bufo", but are now separated into various other genera such as "Anaxyrus" and "Incilius". |

||||||

|

American Toads (Anaxyrus americanus) are found across much of eastern North America. Adults migrate to wetlands in the spring, where males attract females with their distinctive, extended trilling call. The American Toad mating season is a hectic event, with males singing and fighting as females enter the ponds to mate. In some years and some locations, female toads are more likely to mate with larger males, however this is not always the case. There is some evidence that female American Toads prefer males that have a high rate of calling, or lower-frequency ("deeper") trills. |

Adult American Toad next to a mushroom in central Pennsylvania. |

A large American Toad from southeastern Michigan. |

||||

Male American Toad on the edge of a pond during the breeding season. |

An American Toad among the cattails calling with inflated vocal sac. |

A male American Toad with a large leech attached to its side. For some reason, during the breeding season adult toads seem to get attacked by leeches more than other amphibians. |

||||

A male American Toad watches a female toad walk by with a male clinging to her back in amplexus. |

Circular ripples of water radiate away from this calling male toad as his energetic calling vibrates the water. |

|||||

Nuptial pad on thumb of male American Toad. The Nuptial pads help the male cling to the female during amplexus; the presence of nuptial pads can be used to identify the sex of toads during the breeding season. |

A male American Toad clings to the back of a female toad during the breeding season. |

A pair of American Toads in amplexus surrounded by strings of thousands of eggs that the female laid an the male fertilized. |

||||

Moonlight view of a group of breeding American Toads in a Pond. |

|

An American Toad that died during the breeding season, likely due to drowning. |

||||

A string of fresh American Toad eggs. American toad development happens quickly; toads can go from eggs to metamorphosis in a few short weeks |

American Toad hatchlings with external gills still visible. The middle tadpole is from an albino female American Toad. |

An American Toad tadpole with large hind legs. American toads can accelerate their development to escape predators like dragonfly nymphs that feed on toad tadpoles. |

||||

Two tiny juvenile toads hidden in the mud near a mushroom. |

Two juvenile toads perched on a dime. |

Tiny recently metamorphosed toad leaving the pond. A small snail is nearby. |

||||

Portrait of the head of an American Toad from Allegany County, New York. |

American toad from Cuyahoga County, Ohio. |

American Toad blinking. |

||||

Western Toad: Anaxyrus boreas (previously Bufo boreas) |

Western Toad on a hillside, with the Berryessa Reservoir in the background. |

Western Toad in a breeding pool. |

||||

Red-Spotted Toad: Anaxyrus punctatus |

Southern Toad: Anaxyrus terrestris |

Southern Toad with a nice reddish color. |

||||

Woodhouse's Toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii) half-buried in dirt in a hollowed-out log. |

huge Woodhouse's toad seen in New Mexico. |

Curious dog checks out a Woodhouse's toad in New Mexico. The dog sniffed the toad, but did not lick or bite it. |

||||

Duttaphrynus melanostictus, a toad with a variety of common names: Southeast Asian Toad, Asian Common Toad, Spectacled Toad |

Incilius nebulifer Gulf Coast Toad, Coastal Plain Toad |

|||||

HylidaeThe Hylidae are a diverse group of treefrogs, with nearly 1,000 species distributed on all continents except Antarctica. |

||||||

|

In the continental United States and Canada, there are three genera of native treefrogs: Acris, Hyla, and Pseudacris. The Cuban Treefrog has been introduced to the US and become established, adding a fourth genus: Osteopilus. |

Cricket Frog (Acris crepitans) |

|||||

|

Spring Peepers (Pseudacris crucifer) are one of the best-known harbingers of spring in eastern North America. They are one of the first frogs to call as snow changes to rain, and their loud "PEEP!" can be amplified by hundreds or even thousands of male peepers calling from wetlands. These small frogs are usually some shade of tan, and can be distinguished by the "X" marking across their back. Spring Peepers metamorphose at a tiny size, and can easily fit on top of a penny. Outside of the breeding season, Spring Peepers typically live in forests, and often can be found on damp days hopping around the forest floor. |

Advertisement call of the Spring Peeper. |

|||||

Calling Spring Peeper with vocal sac filled. |

Male Spring Peeper with deflated vocal sac. |

Spring Peeper sitting on top of a mass of ice-killed Wood Frog eggs. |

||||

Male Spring Peeper with dark, loose skin on throat. Throat coloration and skin texture can be used to tell males from females in some species of frogs. |

Female Spring Peeper with smooth cream-colored skin on throat. |

Eggs are visible through the translucent skin on the side of this Spring Peeper. |

||||

One male Spring Peeper chases away a rival. |

A pair of Spring Peepers in amplexus. |

Mating Spring Peepers with newt in background. |

||||

Two male Spring Peepers sitting next to each other. |

A recently-metamorphosed Spring Peeper perching on a penny. |

Spring Peeper tadpole close to metamorphosis with large hindlimbs. |

||||

|

Pacific Chorus Frogs (Pseudacris regilla) are widespread in western North America, and famously appear as frog sounds in Hollywood movies and even popular music. Within their native range, Pacific Chorus Frogs can be found in a variety of habitats, including in eagle nests high in trees. These frogs sometimes are carried outside their native range on agricultural products like Christmas Trees. There is an entire page dedicated the the biology of Pacific Chorus Frogs. |

Calling Male Pacific Chorus Frog |

Pacific Chorus Frog |

||||

|

Midland Chorus Frogs (Pseudacris triseriata) are found through much of Michigan, Ohio and Illinois, with some distribution into surrounding states. In much of their range, they are one of the first frogs to begin calling every year, along with Spring Peepers and Wood Frogs. Their call is a clicking trill, reminiscent of the sound made when you rub a finger along a comb. |

caption |

caption |

||||

|

Green Treefrog (Hyla cinerea) are found in much of the southeastern United states from Texas through Maryland. Male Green Treefrogs have an interesting (some would say "amusing"; others would say "annoying") honking call. |

A male Green Treefrog with vocal sac extended while calling near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina one wet August night. |

A male Green Treefrog being eaten by a ribbon snake on a warm July night in Florida. Calling male frogs with their loud songs and conspicuous behavior can attract predators as well as females. |

||||

|

There are two species of Gray Treefrog in North America: the Cope's Gray Treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and the Gray Treefrog (Hyla versicolor). These two species are found across much of eastern North America, and they cannot be told apart by their physical appearance. They differ in how many chromosomes they have. Cope's Gray Treefrog is diploid with 24 chromosomes, and the Gray Treefrog is tetraploid with 48 chromosomes. The Gray Treefrog originated as a new species through polyploid speciation when an ancient event caused a doubling of the number of chromosomes in Cope's Gray Treefrog. These two species can be told apart by the males' call. Cope's Gray Treefrog calls are a more rapid trill than those of the Gray Treefrog. |

A male Gray Treefrog makes its distinctive trill. |

|||||

Gray Treefrog living in a hole in a tree high above the ground. |

Gray Treefrog living in a dumpster, where it gets plenty of flies to eat. |

Close-up of the dumpster-diving Gray Treefrog. |

||||

"Bubble-Head" |

Male Gray Treefrog calling from the pond. |

Mating Gray Treefrogs in amplexus. |

||||

Flash color on the hind legs of a Gray Treefrog. |

Gray Treefrog in a perch on a plant. |

Gray Treefrog hanging onto a finger. |

||||

Gray Treefrog Tadpole. The bright red tail is an example of predator-induced phenotypic plasticity. |

Gray Treefrog tadpoles showing predator-induced red tail color compared to tadpole without predator-induced color. |

|||||

Male Gray Treefrog calling from a tree with its vocal sac extended. |

Video explaining the difference in calls between Cope's Gray Treefrog and the Gray Treefrog. |

|||||

|

The Cuban TreeFrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) was introduced to the United States from Cuba at least as early as the 1920s, if not earlier. They are frequently moved around in horticultural material. While they are impressive-looking treefrogs, they can harm native amphibians and other animals. |

This Cuban Treefrog showed up in a flower store in Cleveland, Ohio. |

Front portrait of the Cuban Treefrog that arrived in Cleveland. |

||||

RanidaeThe family Ranidae is composed of over 400 species with a nearly worldwide distribution. In North America, these can be thought of as our "typical frogs" or "water frogs", although some of them spend most of their lives away from water. Here, I use the genus "Rana" for all of our North American ranid frogs. However, the taxonomy of these frogs was thrown into chaos in 2006 when a group of amphibian biologists published a 371-page paper that re-arranged the taxonomy of many amphibians. This was a controversial opinion, with many criticisms of the methodology. In 2016, another group of researchers conducted another analysis of the evolutionary history of the amphibians, and argued for the restoration of the genus "Rana" for North American members of Ranidae. Following this more recent research, and consistent with amphibiaweb, I will use the genus Rana rather than Lithobates. |

||||||

|

Green Frogs (Rana clamitans) are found in much of eastern North America. They are one of our larger frogs, but don't get as large as American Bullfrogs. Greenfrogs have a distinctive call like the sound of someone plucking a banjo string. I think of their call as one of the sounds of summer. From May through August, day and night, I regularly hear the twang of the Greenfrog's call when I am near wetlands in the midwest. |

An example of the generalist nature of green frogs, this video shows an adult green frog hanging out in a vernal pool eating wood frog tadpoles. One of the interesting aspects of this is that green frogs typically don't breed in these kinds of vernal pools. Because these pools dry out every year, and green frog tadpoles typically take at least a year to metamorphose, any green frog eggs laid in this pond would not survive to metamorphosis. Yet green frogs still visit these vernal pools to feast on the wood frog tadpoles. |

|||||

Male Green Frog. The size of the eardrum (tympanum) can be used to tell males from females in some species of frog. The large tympanum indicates that this Green Frog is a male. |

Female Green Frog: note the small eardrum (tympanum) behind the frog's eye. The small size tells us that this is a female frog. |

Green Frog sitting on a log. |

||||

Looking into the eyes of a Green Frog tadpole. |

||||||

|

American Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana ) are native to eastern North America, but have been introduced to other parts of North America and around the world (e.g., Africa, Asia, Europe). They get very large, and their prey includes insects, birds, mammals, reptiles and other amphibians. Their large size and hearty appetites combine to cause problems for native species. Bullfrog females can lay over 20,000 eggs. In very warm weather, their tadpoles can metamorphose within a year. But in cooler environments, including much of their native rage, the tadpoles will usually take one or two years to metamorphose. Thus, the tadpoles spend at least one winter in ponds, sometimes two. Their tadpoles are also distasteful to fish, allowing them to co-exist with fish when many other amphibians can't. |

Bullfrog with a damselfly perched on its eye. |

Bullfrog floating in a pond in Livingston County, Michigan. |

||||

Bullfrog |

Female Bullfrog |

Large Bullfrog tadpole. |

||||

Bullfrog tadpole. |

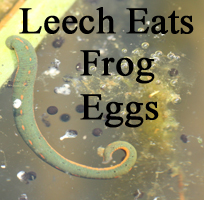

A large leech eats some fresh American Bullfrog eggs. |

|||||

|

Pickerel Frogs (Rana palustris) have a patchy distribution throughout much of eastern North America, with large gaps in some regions. They often breed shortly after the wood frog breeding season, but before many of the summer-breeding frogs, like bullfrogs and green frogs. |

Young Pickerel Frog |

Pickerel Frog in small, shallow stream. |

||||

Pickerel Frog Tadpole. |

Metamorphosing Pickerel Frog Tadpole. The pattern of squarish blotches are beginning to appear on the back. |

Belly-view of a metamorphosing Pickerel Frog. The mouth has not yet fully changed from the tadpole mouth to the adult frog mouth. |

||||

|

The Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens) is one member of a group of leopard frog species. It is similar in appearance to the Pickerel Frog, but the spots on its back are more irregular in appearance. It also has an early breeding season, and its tadpoles metamorphose after a couple months. |

Metamorphosing Leopard Frog. |

Adult Leopard Frog on moss. |

||||

| Wood Frogs (Rana sylvatica) are quite remarkable. They are found the farthest north of any North American amphibian, with populations found above the Arctic Circle. However, they are also found as far south as Alabama. Wood Frogs are one of the few amphibians that are able to survive being frozen for several months. Interestingly, warm winters can be bad for Wood Frogs. When winters are warm, they may expend too much energy during hibernation, and warm winters can even reduce the number of eggs Wood Frogs produce. |

Female Wood Frog with a reddish coloration. |

|||||

Photo showing Wood Frog amplexus, in which male wood frogs cling to the females during mating. |

Two pairs of mating wood frogs floating next to some old and new eggs. The old eggs had been killed in a sudden freeze. |

Underwater view of wood frog egg masses. The embryos are well developed and approaching hatching. . |

||||

Wood Frog hatchling in profile. |

Wood Frog Embryos can be seen rotating within their egg membrane in this video sped up 15 times. The occasional twitches of the embryos cause some of the movement. However, the embryos' movement is also caused by epidermal ciliated cells. These are are hairlike structures on the embryo's skin. Waving cilia help embryos breathe, and contribute to drift within egg membranes. The epidermal ciliated cells with be lost soon after hatching. |

|||||

Recently hatched wood frogs sitting on top of their old eggs. Look closely, and you can see the feathery gills still visible behind the tadpole's heads. Soon the tadpole's skin will grow over the gills and they will not be visible. |

Video showing some of the dangers that wood frog tadpoles face |

|||||

Two wood frog tadpoles; one is on top of the leaf litter while the other is peeking out from under the leaves. |

A wood frog in the process of metamorphosing. It has all four limbs, but is still absorbing its long tadpole tail. |

A juvenile wood frog sitting next to Partridge Berry a few weeks after it metamorphosed from the tadpole stage. |

||||

An adult wood frog sitting on moss. |

||||||

ScaphiopodidaeThe family Scaphiopodidae is confined to North America, and contains seven species spread across two genera: Spea and Scaphiopus. |

||||||

A Couch's Spadefoot Toad partially burrowed into the sand. |

Close-up view of the eye of a Couch's Spadefoot Toad. |

New Mexico Spadefoot Toad |

||||

A Western Spadefoot in the water of its breeding site. |

Another Western Spadefoot in the water of its breeding site. |

Western Spadefoot that has recently emerged from the ground. You can still see the earth clinging to its skin. |

||||

| Tweet |

| |||||||||||||||